When the Jews initially entered the village he was with his mother in the cave. After several hours of allowing the women to return to their homes, he returned with his mother from the cave at which point a passing army patrol spotted the woman and her son. The soldier shouted to her, "Where are you going and why is this (her son) here." The mother replied pleading that her son was young and had nothing to do with the war. The soldier demanded the mother turn over her son to them and after her refusal they grabbed him by force from his mothers arms. The woman was crying and weeping desperately but to no use. After the soldiers distanced themselves about 20 meters from the woman, they yelled at the woman saying, "You'll see why we took him." And in front of the mother's eye's the soldier raised an axe and hit the boy directly over the head, slicing his head in two and killing him instantly. The soldier then shouted, "Go and tell the others what you have seen."

--translation of the testimony of an Abu Shusha villager.

At the dawn of 14 May 1948, as the first light of day began to reveal itself, the muezzin called "Prayer is better than sleep" and while through the plains and valleys the echo of the call "Allahu Akbar" rang out, the units of the Zionist Givati brigade began their final assault on the village of Abu Shusha east of the Palestinian town of Ramleh. The object of the military operation was to occupy the village and deport its Palestinian inhabitants.

This was the beginning of the "unknown massacre" in which around sixty Palestinian men, women and children were killed. A lucky few were killed defending the village. Others, however, were rounded up after the fighting was over and shot en masse. Some were reportedly killed with axes.

The residents of Abu Shusha witnessed the arrival of Jewish reinforcements at the neighboring settlement of Kibbutz Gezer the day before the massacre. Everyone in the village realized with fear that their "midnight hour" was upon them, and that the final assault on their village was near. The assault was to follow months of minor skirmishes between the Jewish settlers of Kibbutz Gezer and other Zionist communities in the area and Palestinian villagers. Jewish settlers had previously suggested a non-aggression pact with Abu Shusha. However, the main purpose of such proposals was to play for time giving the leaders of the Haganah the space to concentrate their military force on other fronts in the early stages of the war. The other purposes of such agreements was also to create deeper divisions among the villagers concerning the agreements. The villagers of Abu Shusha had already rejected such proposals.

At the height of the massacre, the scene in Abu Shusha was a bleak one, mirroring the general picture in Palestine at that time. On the same day--13 May 1948--two days before the announcement of the independence of the State of Israel, and before the decision of the Arab government to send their armies to Palestine, Palestinian society was on the point of collapse.

As British soldiers prepared to evacuate the country the administrative structures of the Mandate government crumbled. The Palestinian leadership had never been allowed by the British to prepare themselves to inherit the mantle of government. While the Jewish community had created a state-in-waiting, the Palestinians had been excluded from the decision-making process and positions of power by the Mandate authorities. This situation led to a sense of anarchy in Palestinian circles, uncertainty about the future and a vacuum in the political leadership and organizations. All these issues contributed to a growing sense of panic.

On the military front, the Palestinian were unable to mount their own defensive. They did not possess substantial stocks of arms and ammunition. The level of military organization and preparedness was almost nil. The only exception to this was a couple of thousand armed men led by Abdul Qadr al-Husseini gathered together under the banner of jihad muqadis (holy struggle).

The war situation, after the Deir Yassin massacre on 10 April 1948, entered a new phase. This phase was heralded by a change in Zionist military strategy--the threat or act of massacre--as a means of forcing many thousands of Palestinians to flee their villages and homes in fear of their lives. These villagers followed on the heels of thousands of middle-class and wealthy Palestinians who had already left their homes and moved to more "secure" Palestinian areas in other parts of the country.

One defeat after another, one massacre after another, fear and panic characterized the whole of Palestine. Thousands fled trying to protect their own lives as well as those of their children and loved ones. On April 17th, the town of Tiberias fell amidst similar scenes of panic, and all the Palestinians were compelled to flee. Within days of this happening, a similar course of events took place in Haifa. Thousands of Palestinian inhabitants left. Within a week only a few thousand remained. They were moved to a single neighborhood in the city. On 13 May 1948--when the Zionist forces were preparing to occupy Abu Shusha--the defeated leading citizens of Jaffa signed an unconditional surrender with the forces of the Haganah.

Although the picture was bleak and consequences of the events forced the choice of either death or exile, the residents of Abu Shusha, who then knew the fate that awaited them, arranged a meeting. They decided to stay in the village and defend their homes and lands, and to protect the tombs and burial places of their forefathers.

It was not an easy decision for the village to reach. It followed a short but passionate debate, with the spectre of Dayr Yasin present throughout the discussions. Some argued for an evacuation of the village, believing that their exile would be short-lived. The majority, however, argued, for remaining in the village and protecting it. The villagers then had to decide how to defend themselves in the imminent conflict. The debate centered on two options: the first was to evacuate the women, children and the aged and let the fighters remain. The second option was to let the women, children and aged remain but to hid them in the village caves. The later option was chosen.

The villagers then set about organizing themselves for the forthcoming battle. There were about seventy rifles in the village, 20 of which were old-fashioned muskets. The villagers also had in their possession the old machine gun sent by the famous Arab leader Hassan Salameh, as well as some mines. The fighters positioned themselves around the village and its borders. They began their wait filled with fear and trepidation, and some families even attempted to flee under the cover of darkness rather than face the imminent conflict. However these families were discovered by other villagers and returned to village.

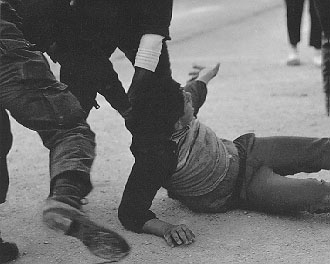

The assault itself began with heavy bombardment by mortars shells from the Jewish artillery. Many houses and streets were damaged in the initial onslaught. By 9 am, Zionist soldiers advanced on the village. The fighters of Abu Shusha tried to repeal the attack, and some were killed in defense. Their lines, however, were easily broken as their arms were no match for the efficiency of the Zionist forces. Some of the fighters stationed on the village boundary line were disarmed and executed by the Jewish fighters as they took the village. Other unarmed villagers fleeing to the east were captured and killed, unable to defend themselves. Once the village had been occupied, the Zionist forces began the process of cleansing the village of its Palestinian inhabitants. Villagers were killed on the street or in their homes. Some were axed to death and others were shot. In one of the houses the Jewish fighters found a group of men and killed them with axes. In front of another house some men were lined up against a wall and executed. This apocalyptic scene was repeated throughout the village and continued until a deathly silence announced the "victory."

However this was not the end of the tragedy. Further chapters remained, as the soldiers were informed that some villagers had hidden themselves in nearby caves. They discovered the caves two or three days later when they found a woman forging for food in her house. The frightened women led the soldiers to the caves where the inhabitants were order to leave. A few men hid in the far recesses of the cave in order to escape detection, making their escape later. With fear in their eyes, squintin in the sun after days in the caves, the remaining villagers came out of hiding. A terrible scene greeted them. The bodies of the slain fighters had been left unburied in the hot May sun. Their bodies were swollen and decomposing, maggots and flies ate their flesh. The woman saw the bodie of their relatives, their husbands, sons, brothers and uncles.

In this terrible moment, the women faced an uncertain future. The only man among them was too old to help, and soldiers made him raise a white flag of surrender over the village. These women, who in the past had risen early to feed their family, who had worked in the fields, and who had laundered clothes, baked bread, and raised their families, were forced to cope with organizing the burial of the dead.

The women formed a committee and asked for permission to bury the dead. They undertook the grisly task with tears in their eyes. They found it impossible to dig in the hard ground, and there was no-one available to conduct the burial service or recite the prayers. Thus the men were buried where they had fallen rather than in the village graveyard. The women threw the bodies in ditches or covered the corpses with soil and stones. The most shocking scene for them was when they reached the house where the men had been butchered with axes.

The tragedy continued. One soldier spotted a woman and her thirteen year old son trying to escape. The boy was axed to death as the woman's cries for mercy rang out through the air. The soldiers also killed an old woman, and mines planted by Jewish forces exploded, blowing the feet off two women.

Ironically, four hours after the massacre, the Jewish People's Council was meeting in Tel Aviv. Those present were there to draft the Declaration of Independence for the new State of Israel. In this declaration the Arab citizens of the state were promised full and equal citizenship and representation in all state structures. However, the villagers of Abu Shusha--themselves now citizens of the new state--were denied any rights, and their forceful expulsion meant they had no place in the state-in-making. They were forced from lands which legally belonged to them. They became homeless and penniless refugees compelled to settle elsewhere.

Material compiled by Rami Nashashibi, June 1996.

Page design by Birzeit Web Team, March 1997.

Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society, Birzeit University, P.O. Box 14, Birzeit, West Bank, Palestine.

Tel: +972-2-998-2975, Fax: +972-2-995-2975, E-mail: center@research.birzeit.edu.